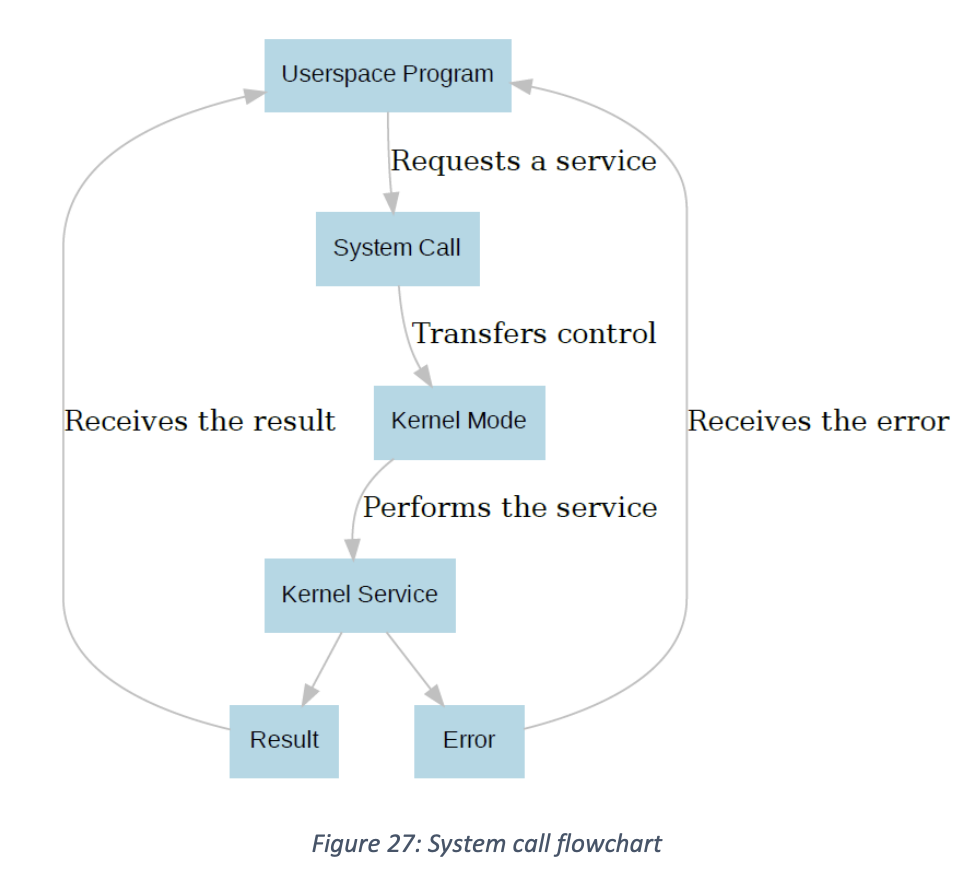

System calls give userspace programs the ability to ask the kernel to do something, since they don’t have access to hardware (like writing a file).

The kernel may refuse, depending on how it is written and what the system call is. For example, in Linux, if a file is already open in one process it cannot be deleted by another. The open and delete operations on that file were both handled via system calls, and the OS enacted a rule that says “you cannot delete an open file” when the delete call came in.

Practically, a system call is simply a function, typically accessed via an interrupt. The function that defines a system call does not get compiled into the user program’s code. Rather, it lives in a fixed place in memory.

Let’s see how this works.

- When you trigger a system call, the system call handler is called to provide a kernel service. Since the handler is always at the same location in memory, the mechanism by which we trigger a system call just needs to know that address, and then call the function pointer stored there.

- In this way, a userspace program can call a kernel function without having to have it compiled into that userspace program – it’s always at the same fixed address, so the userspace programs simply need to know that address. In general, it looks like this:

SVC Function

SVC is the system call function for the Cortex M4.

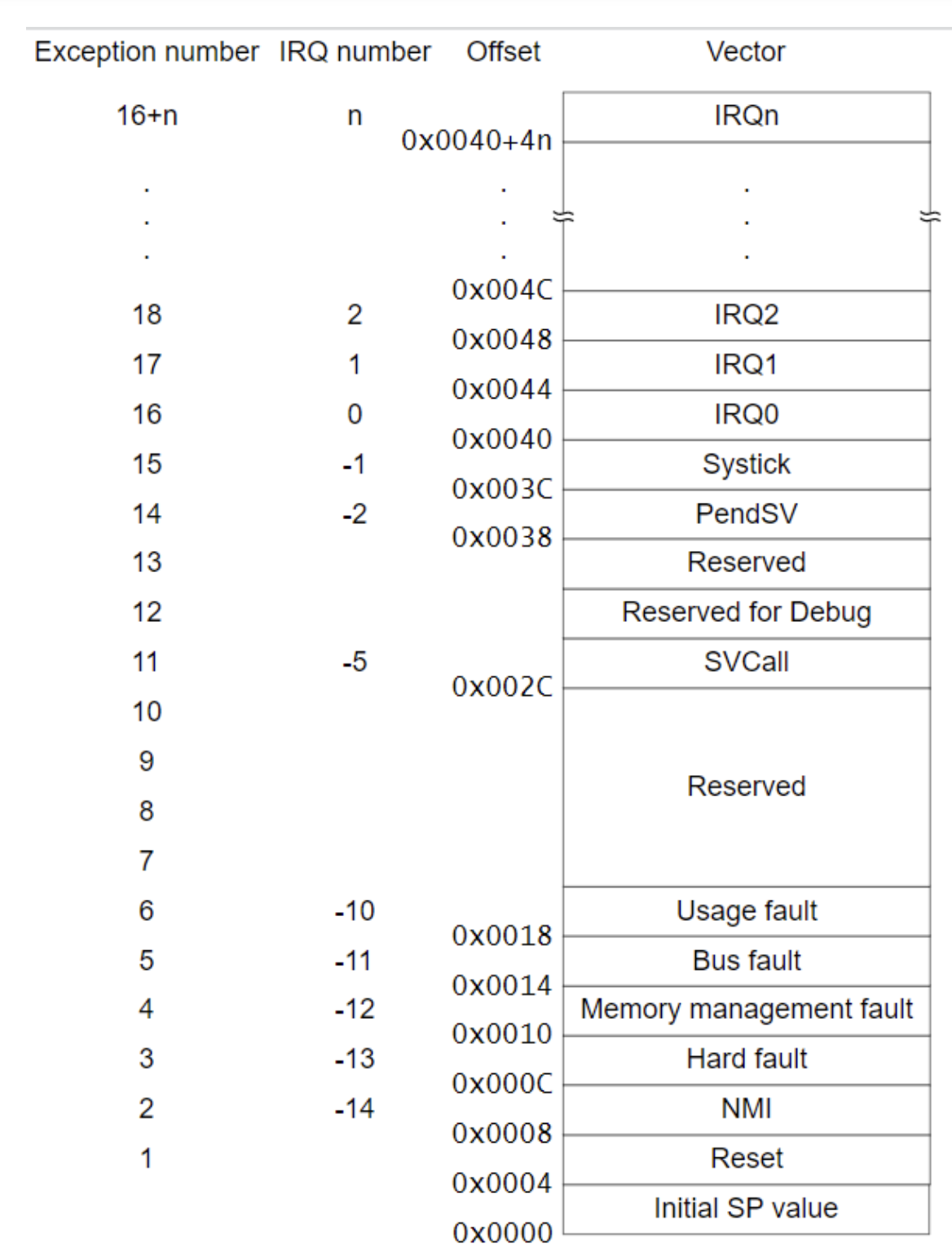

Looking at the Reset Vector Table, we can see that address 0x002C has a label SVCall. We put a function pointer into that address, which serves as the entrance point to system calls.

On the Cortex, this function would be an interrupt function, so it needs to be written at least partially in assembly. In C, we trigger the function via the following assembly code:

__ASM("SVC #1")The number can be anything from 0 to 255. Then:

- An interrupt triggers (SVC is an interrupt instruction on the Cortex)

- That interrupt calls the function stored at address

0x002C - At this point, we are in the kernel and may perform the system call.

- The number passed in with the SVC instruction is the call number. For instance, perhaps system call 0 is “request more memory” and system call 56 is “print to the UART”. It doesn’t matter.

- The kernel unpacks the system call number and takes appropriate action depending on the call. Usually this part is written in C.

- The system call completes and control is returned to the function whose address was stored in

0x002C. The appropriate steps are taken to return from an interrupt, and userspace programs resume.

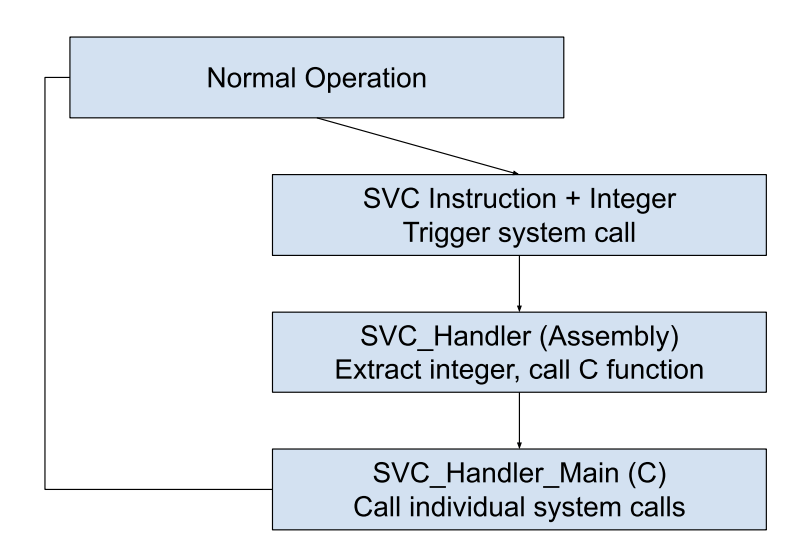

When writing our OS, we want to get out of the 0x002C function, which we’ll call SVC_Handler, as quickly as we can, because writing system calls in assembly is hard to. For this reason, we usually write a function called SVC_Handler_Main, written in C, that receives the system call number and handles all of the work of the real system call. SVC_Handler_Main then returns to SVC_Handler, which is responsible for returning safely from the interrupt mode. It looks like this:

Once we have triggered the SVC the operation of the chip transitions to privileged/kernel mode. This means that the kernel has to do a lot of checking in its SVC handling functions to make sure that the program that requested the system call is even allowed to have it.

SVC_Handler_Main

It’s just a giant if statement. It receives the system call number. Once it has it, it just checks what it is and executes the appropriate function. For instance, let’s say that system call 0 calls a function open_output(), whose job it is to open a UART channel for output to the terminal. That part of the function would look like this:

if(svc_number == 0) open_output(); That’s it! Like I said above, in a larger OS you probably want to at least check to make sure that privileges are set right, but otherwise the logic is relatively simple in this function.

Userspace data sharing

Can userspace programs pass data into and receive data from system calls? Yes, but we have to set up shared memory areas or rely on some other message passing architecture.

In the simplest form, each program gets a unique area of memory that only it is allowed to access. Each program already needs its own stack, but this memory region is special in that its sole purpose is communicating with the kernel.

- If the userspace program needs to give data to the kernel, it either writes the data into this area or it writes a pointer to memory that contains the data (if, for instance, the shared memory area is too small).

- If the kernel needs to give data to the program, it does the same thing. Since both the program and the kernel know which system call has been used, the system calls then get written to use this shared memory region or not, depending on what they are.)

The shared memory areas need to be very strictly protected! If anyone can write to anyone else’s memory area, then system calls will go haywire.