We want to isolate issues about thinking procedurally. Let us consider that the interpreter itself is following a procedure to evaluate a combination using the following rule:

- Evaluate subexpressions of the combination.

- Apply the procedure denoted leftmost subexpression (the operator) to the arguments that are the values of the other subexpressions (the operands).

The first step dictates that in order to accomplish the evaluation process, we must first perform the evaluation process on each element of the combination. Thus, the evaluation rule is recursive in nature; to apply the rule, you needs to invoke the rule itself!

This idea of recursion can be expressed succinctly by a nested combination:

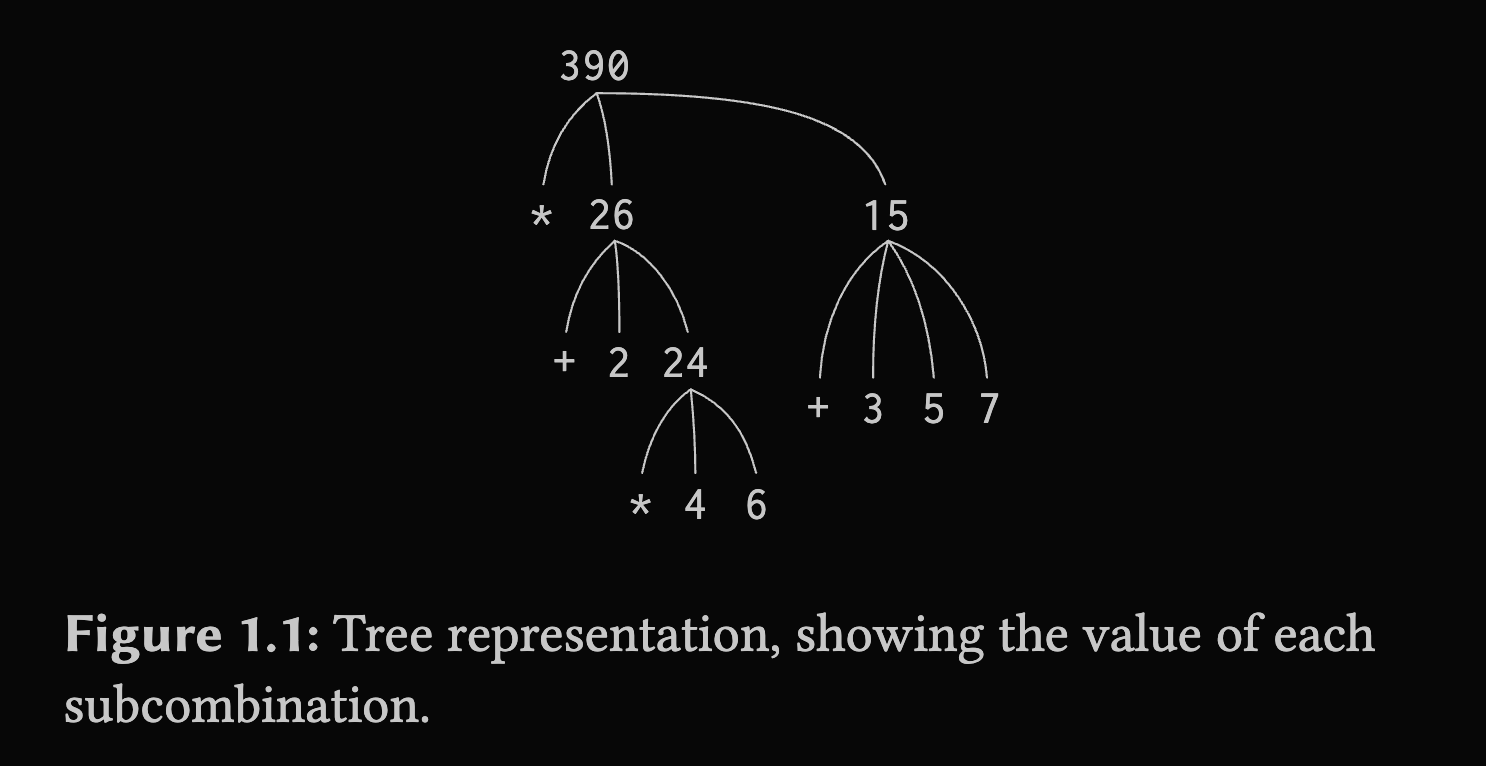

(* (+ 2 (* 4 6)) (+ 3 5 7))This can be thought of as a tree structure:

Viewing evaluation in terms of the tree, we can imagine that the values of the operands percolate upward, starting from the terminal nodes and then combining at higher and higher levels. In general, this process is called tree accumulation.

Observe that the repeated application of the first step (evaluate subcombinations) brings us to the point where we need to evaluate, not combinations, but primitive expressions such as numerals, built-in operators, or other names. We take care of the primitive cases by stipulating that

- the values of numerals are the numbers that they name,

- the values of built-in operators are the machine instruction sequences that carry out the corresponding operations, and

- the values of other names are the objects associated with those names in the environment.

Special Forms

There are certain cases that don’t follow the evaluation rules. For example, the evaluation rule given above does not handle definitions. For instance, evaluating (define x 3) does not apply define to two arguments, one of which is the value of the symbol x and the other of which is 3, since the purpose of the define is precisely to associate x with a value. (That is, (define x 3) is not a combination.)

Special forms each have their own evaluation rules.