When a surface is submerged in a fluid, forces develop on the surface due to the fluid. For fluids at rest we know that the force must be perpendicular to the surface since since there are no shearing stresses present. We also know that the pressure will vary linearly with depth if the incompressible.

Horizontal Surface

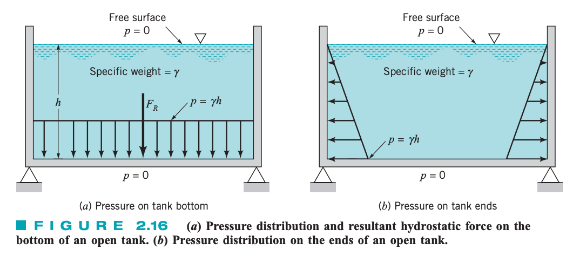

For a horizontal surface, such as the bottom of a liquid-filled tank, the magnitude of the resultant force is simply

F_{R}=pA $$where $p$ is the uniform pressure on the bottom and $A$ is the area at the bottom. - For the open tank shown, $p=\gamma h$. Note that if atmospheric pressure, then the resultant force on the bottom is simply due to the liquid in the tank. Since the pressure is constant and uniformly distributed over the bottom, the resultant force acts through the centroid of the area as shown. To determine the vertical surface, we can consider the more general inclined case. ## Inclined Surface When the submerged plane surface is inclined, the determination of the force is more complex. For the present we will assume that the fluid surface is open to the atmosphere. ![[Hydrostatic Force on a Plane Surface-1.png|439]] Given: - Let the plane in which the surface lies intersect the free surface at 0 and make an angle $\theta$ with this surface as shown above. - The $x$-$y$ coordinate system is defined so that $0$ is the origin and $y=0$ (the $x$-axis) is directed along the surface as shown. - The area can have an arbitrary shape. We wish to determine the **direction**, **location**, and **magnitude** of the resultant force acting on one side of this area due to the liquid in contact with the area. At any given depth, $h$, the force acting on $dh$ (the differential area of the figure above) is $dF=\gamma h \, dA$ and is perpendicular to the surface. (This is just force = pressure * area). ### Magnitude The magnitude of the resultant force can then be found by summing these differential forces over the entire surface:F_{R}=\int_{A} \gamma h , dA = \int _{A} \gamma y\sin \theta , dA

where $h=y\sin \theta$. For constant $\gamma$ and $\theta$F_{R}=\gamma \sin \theta \int_{A}y , dA

The integral part of the equation above is the first moment of area about the $x$-axis, so we can write\int_{A}y , dA=y_{c}A

where $y_{c}$ is the $y$-coordinate of the centroid of area $A$ measured from the $x$-axis which passes through $0$. Then, we can re-write the force as\begin{align} F_{R} & =\gamma A y_{c} \sin \theta \ & =\gamma h_{c}A \end{align}

where $h_{c}$ is the vertical distance from the fluid surface to the centroid of the area. ### Location Although our intuition might suggest that the resultant force should pass through the centroid of the area, this is not actually the case. The $y$-coordinate, $y_{R}$, of the resultant force can be determined by summation of moments around the $x$-axis. That is, the moment of the resultant force must equal the moment of the distributed pressure force, orF_{R}y_{R}=\int _{A}y , dF = \int _{A}\gamma \sin \theta,,y^{2} , dA

and therefore, since $F_{R}=\gamma Ay_{c} \sin \theta$:y_{R}=\frac{\int_{A} y^{2} , dA }{y_{c}A}

The integral in the numerator is the [[Second Moment of Area|second moment of area]], $I_{x}$, with respect to an axis formed by the intersection of the plane containing the surface and the free surface ($x$-axis). Thus, we can writey_{R}=\frac{I_{x}}{y_{c}A}

We can then use the [[Mass Moment of Inertia|parallel axis theorem]] to express $I_{x}$ asI_{x}=I_{xc}+Ay^{2}_{c}

where $I_{xc}$ is the second moment of area with respect to an axis passing through the centroid and parallel to the $x$ axis. Thusy_{R}=\frac{I_{xc}}{y_{c}A}+y_{c}

The $x$-coordinate can be similarly derived by summing moments about the $y$-axis:\begin{align} F_{R}x_{R} & = \int {A} \gamma \sin \theta ,xy , dA \[2ex] x{R} & = \frac{\int {A}xy , dA }{y{c}A} \[2ex] & =\frac{I_{xy}}{y_{c}A} \[2ex] & = \frac{I_{xyc}}{y_{c}A}+x_{c} \end{align}

where $I_{xyc}$ is the product of inertia with respect to an orthogonal coordinate system passing through the centroid of the area and formed by a translation of the $x$-$y$ coordinate system. If the submerged area is symmetrical with respect to an axis passing through the centroid and parallel to either the $x$ or $y$ axes, the resultant force must lie along the line $x=x_{c}$, since $I_{xyc}$ is identically zero in this case. The point through which the resultant force acts is called the center of pressure, $C_{p}(x_{R}, y_{R})$. ## Example > [!question] Example Problem > > Determine: > - The magnitude and location of $F_{R}$ > - The moment needed to open the gate > > ![[Hydrostatic Force on a Plane Surface-2.png|401]] > To find the magnitude we can apply:\begin{align} F_{R} & =\gamma h_{c}A \ & = 9.8 \times 10^{3} \frac{\text{N} }{ \text{m}^{3}}\cdot 10 \text{ m} \cdot 4\pi \text{ m}^{2} \ & = \boxed{1.2 \text{ MN}} \end{align}

To find the location $(x_{R}, y_{R})$, we can first note that $x_{R}=0$ since the area is symmetrical and the center of pressure must lie among the line $A$-$A$. We can first findI_{xc} = \frac{\pi R^{4}}{4}

which is just the second moment of inertia for a circle. $y_{c}$ is given to us in part (b) of the figure as $10 \text{ m} / \sin 60\degree$. Then, we have\begin{align} y_{R} & = \frac{I_{xc}}{y_{c}A}+y_{c} \[2ex] & =\frac{(\pi / 4)( 2 \text{ m})^{4}}{(10 \text{ m} / \sin 60\degree )(4\pi \text{ m}^{2})}+\frac{10 \text{ m}}{\sin 60\degree } \[2ex] & = 0.0866 \text{ m}+ 11.55 \text{ m} \[2ex] & = \boxed{11.6 \text{ m}} \end{align}

To open the gate, a moment must be applied to overcome the moment of $F_{R}$:\begin{align} M & =F_{R}\cdot (y_{R}-y_{c}) \ & = 1.2 \times 10^{6}(\text{N}) \cdot \frac{\pi \cdot 2^{4}}{4} \frac{\sin 60\degree }{10\cdot 4\pi} (\text{m}) \ & =1.07 \times 10^{5}(\text{N}\cdot \text{m}) \end{align}