Pressure is used to indicate the normal force per unit area at a given point acting on a given plane within the fluid mass of interest. How does the pressure at a point vary with the orientation of the plane passing through the point?

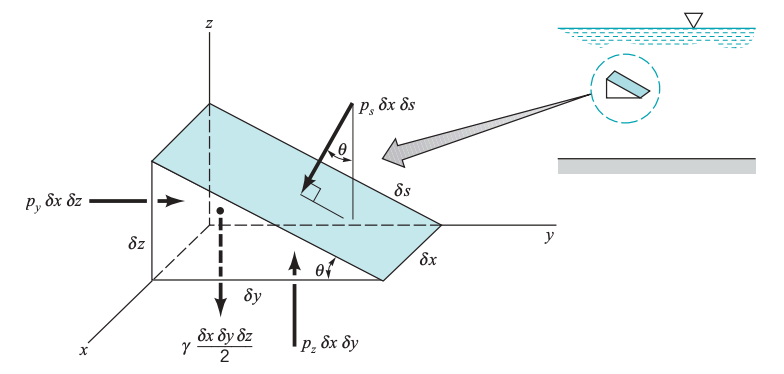

Consider the free-body diagram below, obtained by removing a small triangular wedge of fluid from some arbitrary location within the fluid mass:

Since there are no shearing stresses, the only external forces on the wedge are due to pressure and weight.

- For simplicity the forces in the x direction are not shown, and the z axis is taken as the vertical axis so the weight acts in the negative z direction.

- Although we are primarily interested in fluids at rest, to make the analysis as general as possible, we will allow the fluid element to have accelerated motion.

- The assumption of zero shearing stresses will still be valid so long as the fluid element moves as a rigid body; that is, there is no relative motion between adjacent elements.

Newton’s 2nd law in the and axes give:

where:

- , , and are the average pressures on the faces

- and are the fluid specific weight and density

- and are the accelerations

Clarifying above equations

- Essentially we can just think of the terms as forces in the given direction. Since the terms are lengths, something like is just force in the direction acting on the plane, since pressure = force / area, such that , where .

- Similarly, gives mass, since mass = volume * density.

The equations of motion can be rewritten as:

Since we are really interested in what is happening at a point, we take the limit as approach zero while maintaining the angle, and it follows that

or just . The angle was arbitrarily chosen so we can conclude that the pressure at a point in a fluid at rest, or in motion, is independent of direction as long as there are no shearing stresses present. This is known as Pascal’s Law.