I’ve been working hard lately to get better at certain things. And so, I’ve been thinking about the pursuit of excellence a lot lately. How do I get good at things? Why should I work hard?

This is a collection of thoughts, and may not necessarily well-structured, cohesive, or particularly insightful. I just be yapping man.

The road and the roadblocks

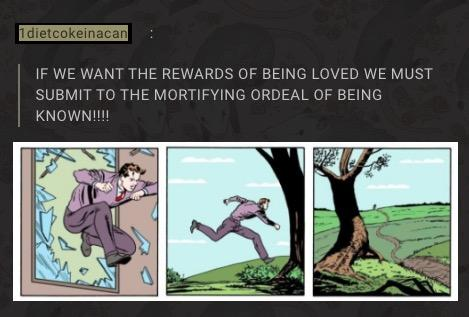

The mortifying ordeal

The first and probably most important step of becoming good at something, and motivating yourself to work hard, is wanting to become good at it. This requires the self-awareness to realize that I am not currently good; in fact, I might even be terrible. This first step can already be challenging – no one wants to be be confronted by their own mediocrity.

(The origin of the phrase “the mortifying ordeal of being known” is shown below, although I’m using it here in a different context than being loved).

Winner’s games and loser’s games`

In some sports, there’s a concept of winner’s games versus loser’s games. Essentially, at different levels of aptitude, the win conditions are different. Let’s take the example of tennis. At low levels, all you really have to do to win is be more consistent than your opponent in hitting over the net and inside the court; you don’t win by being better, you win by sucking less (a loser’s game). At high levels, everyone is consistent, so you win by hitting brilliant shots (a winner’s game).

I feel that this may be bit of a false dichotomy, but the point being raised here is applicable. A huge part of becoming good at things, or at least being better than others, seems to simply be consistency. I think this applies in two ways:

- Consistently showing up and putting the work in.

- Solidifying basics (i.e. consistently hitting over the net and inside the court).

The problem with this is its lack of sexiness. Not many people watch sports to see someone win by being more consistent – people want to see brilliant shots. The same goes for the participant; in the process of practicing, its much more enticing to work on brilliant shots and fancy technique rather than grind out the fundamentals.

Struggling

Another thing that isn’t fun, especially with learning, is that you have to struggle with concepts and techniques before you gain mastery. No one ever became a good tennis player by just reading about tennis, no one ever became good at coding by reading about coding. You don’t do well in a course by copying down the course notes or slides word for word (usually). You have to get your hands dirty, struggle, and probably fail, before you reach mastery. And if you want to keep improving, this never stops.

Easing the pain

Because all of this is the above is so hard, it’s important to think about strategies to make this easier. Most important, I believe in setting proper scopes for goals and making progress measurable. Setting lofty goals that are far away is fine, but it’s best to split large tasks into smaller ones, and add checkpoints in between; grinding away for years with some lofty goal in mind and no measurable progress would make me lose my mind. Having a checklist that you can click when you finish a checkpoint can add a nice little dopamine boost. In some of my notes, especially where I’m working my way through some book, you might see a little progress bar indicating how much of the book I’ve made it through.

People also advocate for another path to making hard work easier for yourself is to learn to enjoy the grind. This is hard. I don’t know if it’s always possible, or possible at all. It might just be cope. I also don’t know if it’s the best way to do things; do you really have to enjoy something to make yourself do it? Obviously it might be better, but sometimes you just need to suck it up and get shit done.

Mirages

In Takehiko Inoue’s manga Vagabond, the protagonist Musashi Miyamoto is single-mindedly driven by his desire to become strong. Not just strong, but the strongest – “Invincible under the Heavens” (天下無雙). Eventually, Musashi realizes that being the strongest is simply an empty title – when asked what it’s like to be invincible by another swordsman, Musashi compared it to a mirage; you can see it so clearly from afar, but it fades when you get close.

This can be interpreted a lot of ways. A big part of my interpretation of this is that becoming good at something – in Musashi’s case, the way of the sword – should not be an end in and of itself. Wanting to be good at something simply for the sake of being good at it, or for external validation, will often lead to a sense of emptiness; why did I do this in the first place? I’ve found that it’s more sustainable to have an external reason for becoming better at something, or have a particular goal in mind; it’s also easier to set concrete goals for yourself along the way, which also helps with scoping!

Mind that you don’t need some deep reasons for doing things, or wanting to become good at things; simple reasons are enough. If doing something makes you happy, what other reason do you need?

Rewards

The obvious reward is that now you’re good at what you wanted to be good at, and hopefully met your underlying goal or reason. But there are some other benefits too.

Compounding Effects

A crucial thing to recognize is that there’s value in working hard in and of itself. In fact, I think that working hard is a learnable skill with superlinear returns. Let’s say I spend years working hard to get good at software engineering. Suddenly, massive improvements in AI make my job obsolete (this may hit too close to home for some). While my software engineering skills are now useless, t’s not a complete loss; I know what it’s like to work hard, and I know that if I’ve done it before, I can do it again. I can bet on myself, and use my ability to do hard work to do something else with my life. Like a muscle, the more I use it, the more I can rely on it in the future.

Serendipity

Similarly, much of the world is based on the same abstractions. Learning a concept in the context of Topic A often turns out to be more useful than expected, when you get to learning about Topic B and have a moment of serendipity – this is just like the concept I learned in Topic A, but under a different name! Now, not only do you learn Topic B faster, the fact that this concept is present in both Topic A and B might lead to some insight about an underlying abstraction. It’ll be easier and easier to recognize this underlying concept in different contexts, and now we have a new tool at our disposal. We might also find ourselves becoming increasingly “lucky”; for example, going into an interview, and they just happen to ask a question that I’ve done before. Luck favors the prepared…

me when i work hard and good things happen: