When we are trying to understand a system with estimation filters but that system is uncooperative, it’s good to have multiple models of the system to account for various different behaviors. This idea is very similar to Mixture of Experts!

Plane Tracking Example

A good example of this is tracking a plane with a radar system, but the plane is uncooperative; we are not in control of the plane and do not know their actions, so our only source of data is radar measurements.

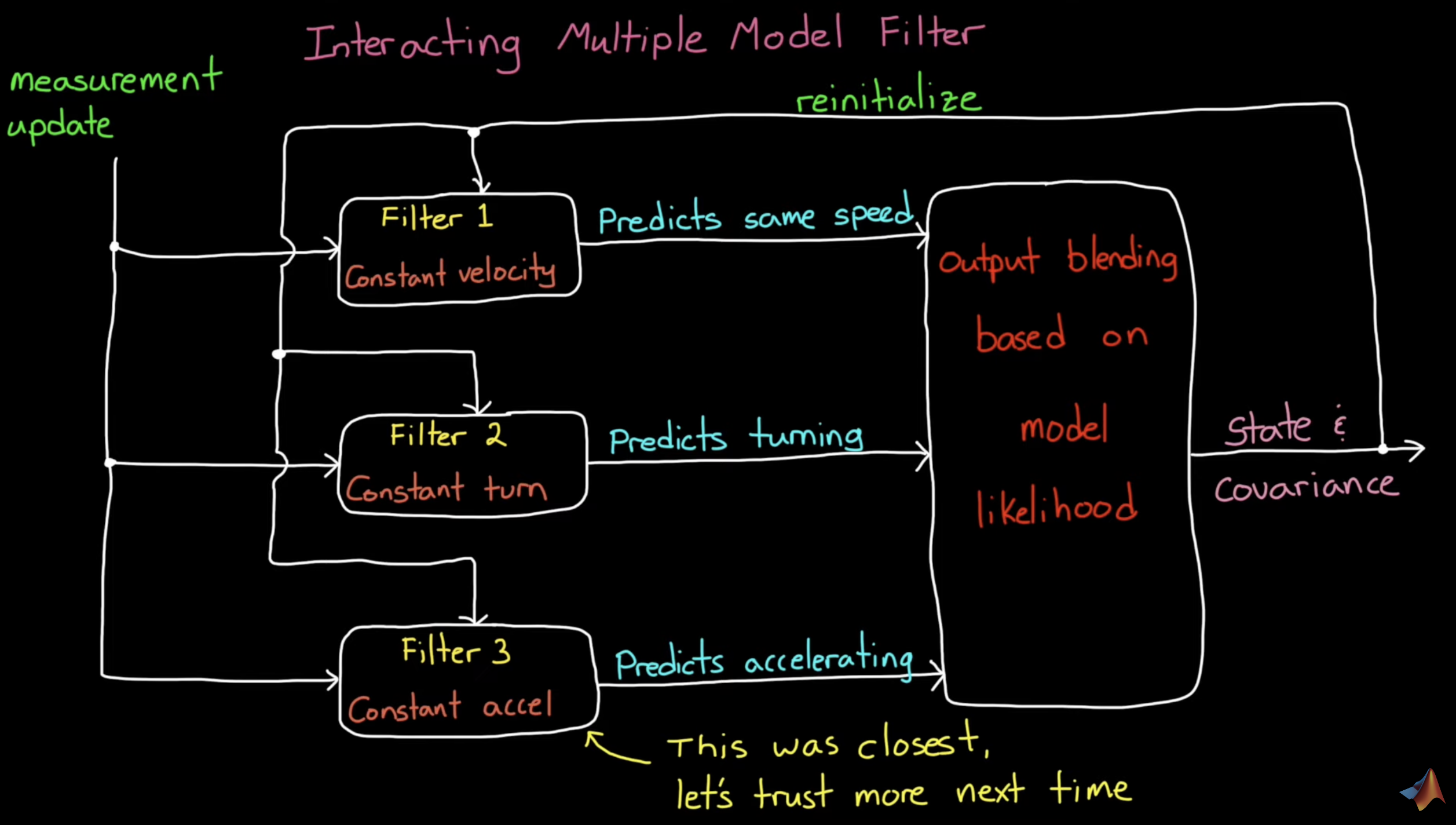

So, we run several simultaneous estimation filters, each with a different prediction model and process noise. We aim to have a model for each type of motion/behavior that we expect: flying with constant speed, constant turning, or constant linear acceleration.

- Each model predicts where the plane will be if it follows that particular type of motion.

- Then, when we get a measurement, we compare it to the different model predictions, which lets us make claims on which models are close to the true motion and which models are not.

- We can then blend our output based on model likelihood determined above.

This method will have some transient error whenever the object transitions to a new motion, but the filter will quickly realize when another model has a better prediction and start to increase its likelihood.

Interaction

The problem we have with the above method is that each filter is operating on its own, isolated from the others. So, for a model that doesn’t represent the true motion, it’s still going to be maintaining its own bad estimate of system state and state covariance. Then, if there’s a transition to this model due to a change in motion, it will take some time to converge again due to its bad estimates, which results in a transient period that’s longer than necessary.

This is fixed by allowing the models to interact.

- After a measurement, the overall filter gets an updated state and state covariance based on the blending of individual model outputs.

- At this point, every model is re-initialized with a mixed estimate of state and covariance based on their probability of being switched to or mixing with each other.

This creates a feedback loop that constantly improves each filter to reduce its own residual error even when that filter doesn’t represent the true motion of the object. Thus, our IMM filter can switch to an individual model without having to wait for it to converge first.