This is the modern approach.

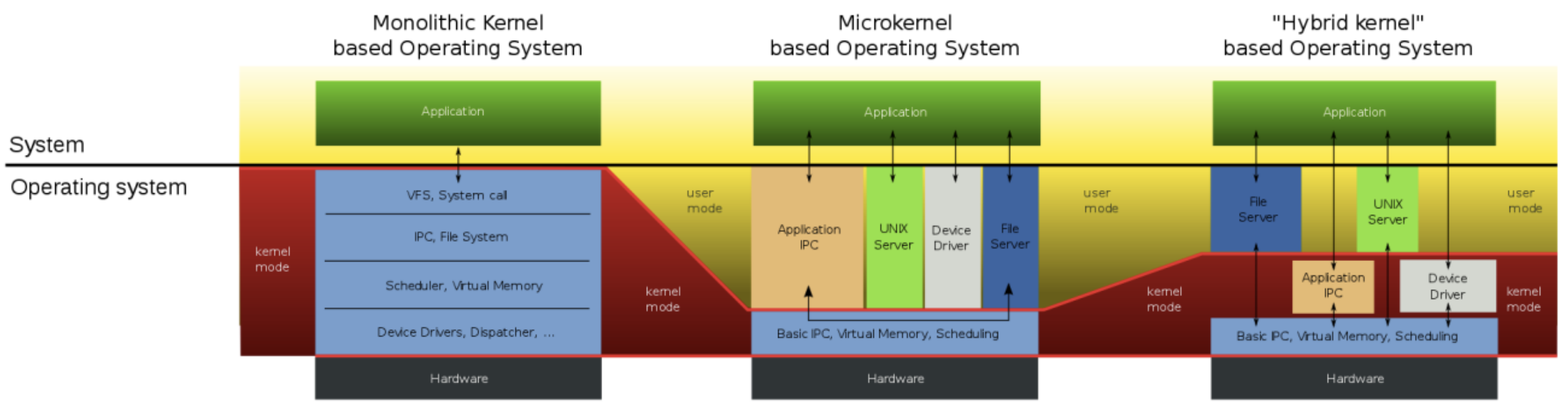

In a Microkernel, almost everything is in userspace with tons of interactions with the kernel slowing everything down. In a Monolithic Kernel, almost everything is in the kernel with tons of space being taken up by edge cases. The modular kernel tries to take advantage of both extremes:

- If something can happen in userspace, it should

- If something is faster or only possible in kernelspace, it should be there

- The kernel should be able to load its own programs, called modules, that expand it

Advantages:

- Staying in userspace whenever possible reduces security issues

- Staying in kernelspace whenever needed increases the efficiency of the whole system, since common, hardware-related tasks can be baked into the kernel directly.

- Allowing the kernel to expand as though we are just installing new software, we don’t need the kernel to ship with absolutely every possible functionality it could ever have.

The downsides of this mostly have to do with complexity and unoptimized efficiency:

- If we allow the kernel to load modules, then someone has to write them. This means that poorly written modules can derail a system even if the kernel is perfectly debugged.

- Since we are taking stuff out of the kernel that now has to be loaded, and offloading some of the functionality to userspace, we are not able to take full advantage of the computer hardware. Things get a bit slower.

- We now have to manage two interfaces – one to the userspace parts and one to the modules, so writing the kernel gets more complicated than it would be if it were monolithic or micro.

However, just because something is hard doesn’t mean that it is a bad idea, and nowadays every modern OS you’ll ever encounter is modular.