AIRBOT

Grasping and manipulation

As part of ELEC 4260 (Intelligent Robots and Embodied AI) at HKUST, I implemented various grasping methods for the AIRBOT Play robot arm:

- Basic grasping of circular objects

- Pose-based grasping with PoseCNN

- Direct grasp detection with GGCNN

Videos:

Basic Grasping

This part of the project involved implementing simple functions for computing pre-grasp, grasp, and post-grasp poses, integrated into a simple grasping pipeline. A circle detector using OpenCV’s Hough Circle Transform was used to identify circluar objects within camera view, which were then converted to grasps. In terms of results, the robot was consistently able to grasp circular objects within its reach, with some occasional failures due to failing to detect a circular object.

Pose-Based Grasping with PoseCNN

To extend grasping to more complex everyday objects other with non-circular shapes, we trained a PoseCNN network to estimate 6D object poses, which were refined and matched with grasp templates and executed. Each part of this pipeline is described below.

PoseCNN Model Implementation and Training

The PoseCNN architecture was implemented following the original paper. It is built upon a VGG16 backbone for feature extraction, producing two feature maps. The network consists of three main branches:

- A segmentation branch for instance-level object detection using \(1 \times 1\) convolutions and upsampling operations, with cross-entropy loss for comparing predicted class probabilities to ground-truth segmentation labels.

- A translation branch estimating object centroids in 3D space, which is architecturally similar to the segmentation branch but for regression of centroid coordinates, using L1 loss as a metric.

- A rotation branch for quaternion-based orientation estimation using RoI pooling to extract features from deteced object regions. The rotation loss is only computed for ROIs that have sufficient overlap with ground-truth bounding boxes.

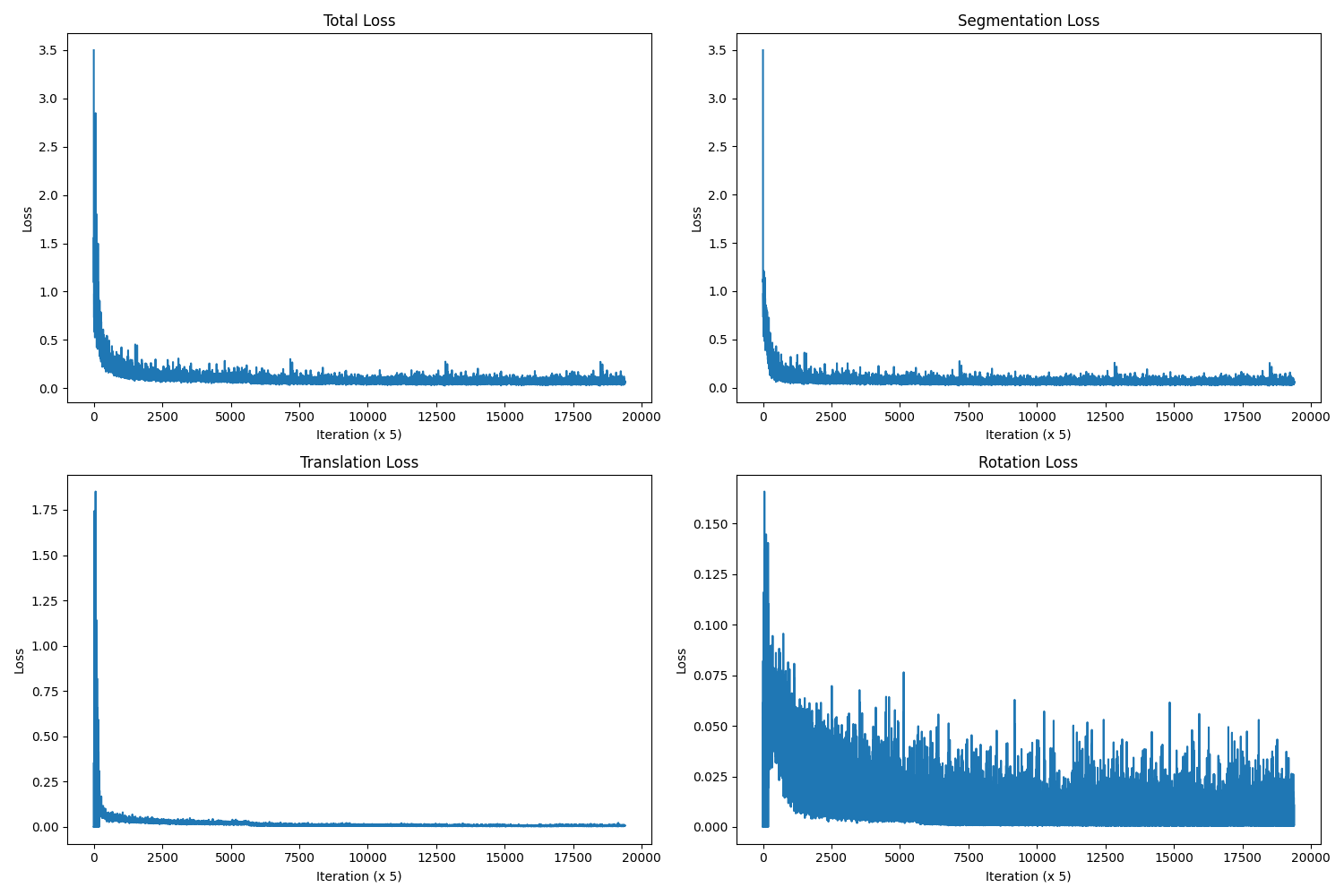

The total loss is simply a sum of the three branches’ individual loss values, allowing all tasks to be learned simultaneously. The training loop in the provided boilerplate code used the Adam optimizer with a constant learning rate of 0.001, with the model being trained for 4 epochs.

I faced several challenges during model training. First, training runs took a significant amount of time (usually 4-5 hours per epoch), which made it hard to iterate and debug. To deal with this, I added gradient scaling for mixed-precision training, casting the model’s operations to FP16 (half precision) where possible, which is faster and uses less memory.

Furthermore, during preliminary training attempts, I noticed that the model rapidly improved at the beginning but did not improve much after a few thousand iterations. Thus, I decided to shorten the training process to 2 epochs, and a OneCycle learning rate scheduler with a lower learning base learning rate; this resulted in much lower loss (from total loss \(\approx\) 0.5 to \(\approx\) 0.2).

Despite these attempts at improvement, the performance of my PoseCNN models were not ideal. I found that the model loss had a tendency to plateau quicly, settling around a total of 0.2; most of this was from the centermap/translation loss, which was usually around 0.13 - 0.15. While the rotation loss had high variance, it was generally very low.

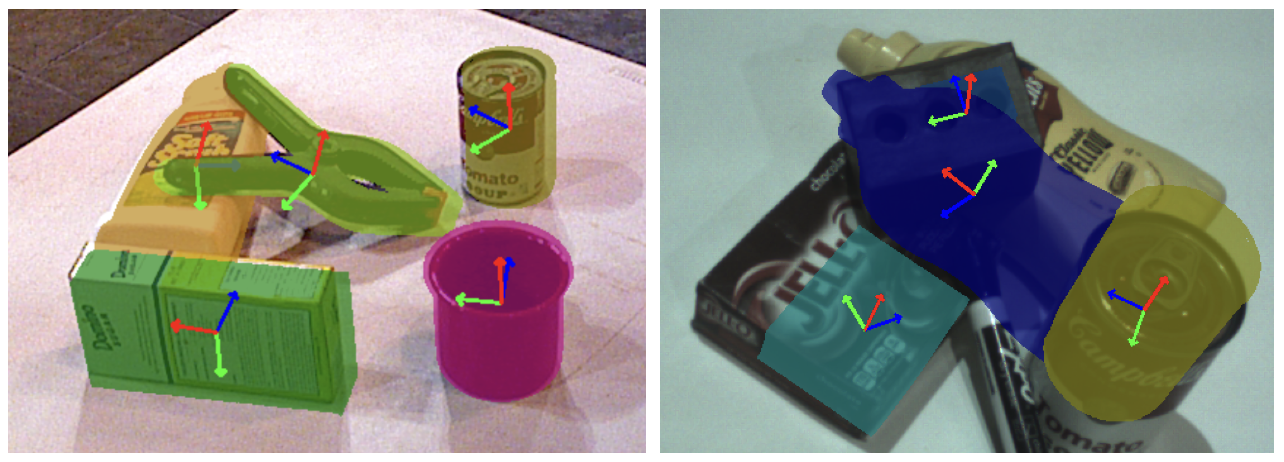

The issues with translation loss were clear during model evaluation and deployment. In an attempt to diagnose these issues, I tried to overfit the model to a single sample and a single scene. In these cases, the model produced perfect predictions (see left side of figure below), with translation loss of near zero. The large translation loss for the model trained on the whole dataset resulted in inaccurate reprojections as shown in the right side of the figure below..

This large difference in performance seems to indicate a lack of model capacity relative to the task; it might also be possible to achieve better results with a set of more ideal hyperparameters, learning rate scheduling, or optimizer. Another possible solution would be to add weighing to the the three loss terms. Given the short time frame for the project I was unable to find such a combination.

Pose Refinement and Deployment

The aforementioned centroid prediction issues were significantly problematic when trying to use the predicted pose to achieve grasping on the real robot; see the left side of the figure below to see the large difference in translation between the predicted position of the object mesh and the actual point cloud. Thus, point cloud filtering and the iterative closest point (ICP) algorithm \cite{icp} were utilized to refine the predicted pose such that it matched the real pose.

Without filtering, I found that ICP would often converge to the wrong solutions, fitting the object mesh model to other parts of the scene, such as matching the flat surface of the bottle to the plane of the table; furthermore, due to the large size of the scene point clouds, ICP would take a long time to run.

After basic cleaning of point clouds (removal of non-finite points), range-based filtering was applied to crop out points that were far away. Then, to filter out the large point cloud plane created by the table, RANSAC \cite{ransac} was used to find the dominant plane in the cloud, which was then removed. This combination of filtering resulted in almost all remaining points belonging to the object, improving the quality and speed of ICP clearly; see the right side of the figure below to see the refined pose compared to the actual objects.

After this pose refinement, I was able to achieve successful grasping with select items. For this task, I set up the camera from a side angle instead of top-down in order to resemble the camera angles in the training set more closely. Despite this effort, this grasping pipeline was still extremely finicky; even in the successful grasp recorded in the video, the arm went through an extra twist to get to the target pose, which meant the target pose may have been upside down from the most optimal target pose. Another note is that I included the pre-grasp offset distance to avoid the gripper knocking over the object while approaching the pre-grasp pose.

Learning-Based Grasp Detection

In this task, GGCNN (Generative Grasping Convolutional Neural Network) was trained in order to directly detect grasps. I also implemented GGCNN2, presented in the journal version of the paper, which achieved slightly better results.

GG-CNN/GG-CNN2 Model Implementation and Training

The GG-CNN model uses an encoder-decoder structure with 3 convolutional layers for encoding and 3 transposed convolutional layers for decoding. On the other hand, GG-CNN2 uses 4 convolutional layers for encoding, dilated convolutions to capture larger receptive fields, and bilinear upsampling instead of transposed convolutions. Both output three predictions: position, orientation (angle of gripper approach represented using cosine and sine components), and width.

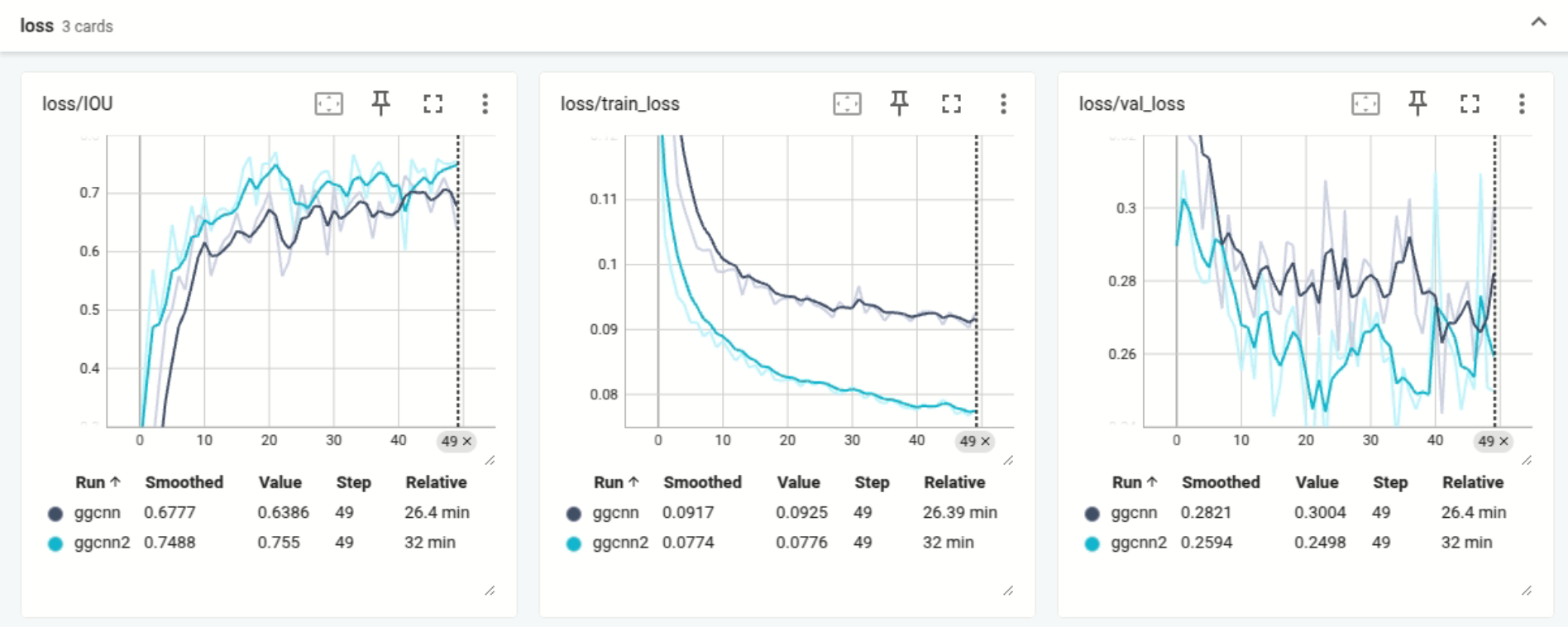

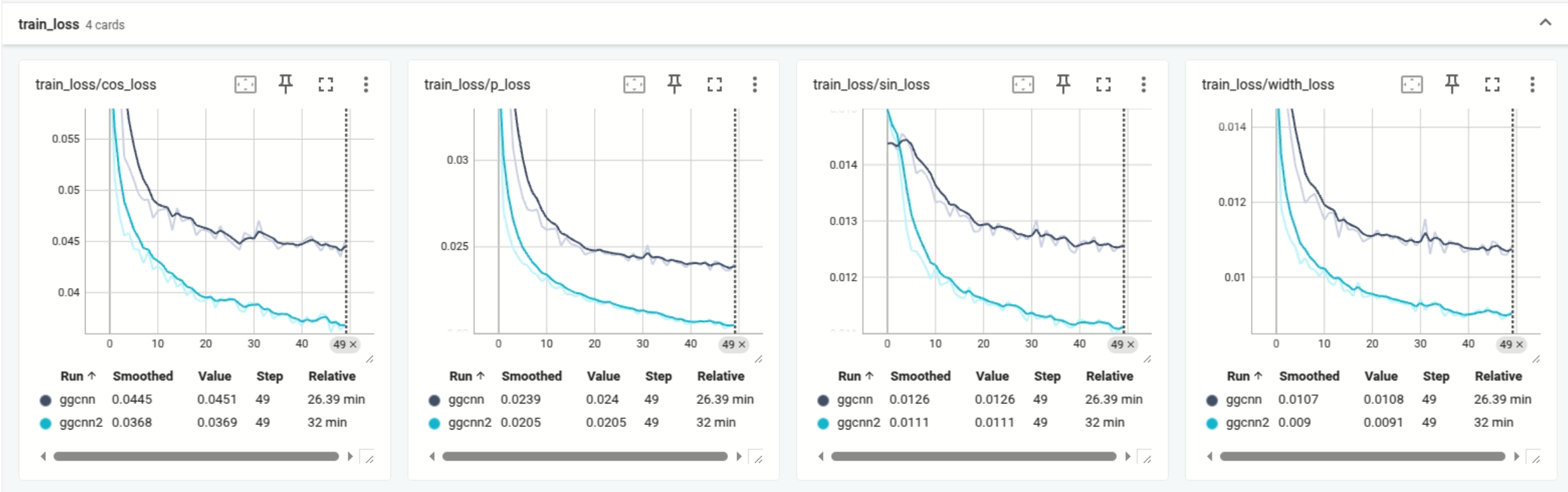

Training for these models was much more successful and straightforward than PoseCNN, achieving decent results in a short time. GG-CNN2 performed slightly better across the board and the two models took almost the same amount of time to train. Loss curves for GG-CNN and GG-CNN2 training are shown in the figures below.

GG-CNN2 Model Deployment

To maximize the chancces of success during deployment, I used the model with the highest IoU (GG-CNN2 model, epoch 33, with IoU = 0.77). I tried to emulate the camera angle of the images in the training set as closely as possible. It took a little bit of extra work to integrate the GraspDetectorNN class with the existig grasp_object script, as this was not provided in the boilerplate.

I tried grasping various objects founda round the lab using the trained network, with varying success.

- Tape roll: 1/10. The model performed quite poorly in this case; this is likely because objects like tape rolls a hole in the middle were not in the training set (at the very least, I didn’t see any while skimming through the images).

- Squash ball: 6/10. This is likely due to the presence of other small round objects in the training data (some sort of fruit?). Since the object is spherical, it may also be more resistant to changes in position as it looks about the same from all angles.

- Remote control: 8/10. There were lots of examples of remote controls and similar objects in the training set, resulting in a high success rate. An example of a successful remote control grasp is shown in the video.